Social media is a perfect vehicle for health education but it is being diverted by fake and damaging content, disrupting preventative health measures and proper treatment. Evidence-based information delivered by trusted organisations and public figures, along with structural changes to social media platforms, are powerful potential antidotes.

Social media is a digital wildfire with the ability to move public opinion and behaviour, but its directionless form is having scorching impact on healthcare. Off-beat treatments, folklore remedies, family traditions and half-truths that defy scientific scrutiny are part of the health landscape, but the internet lets them take flight and spread at a bewildering pace.

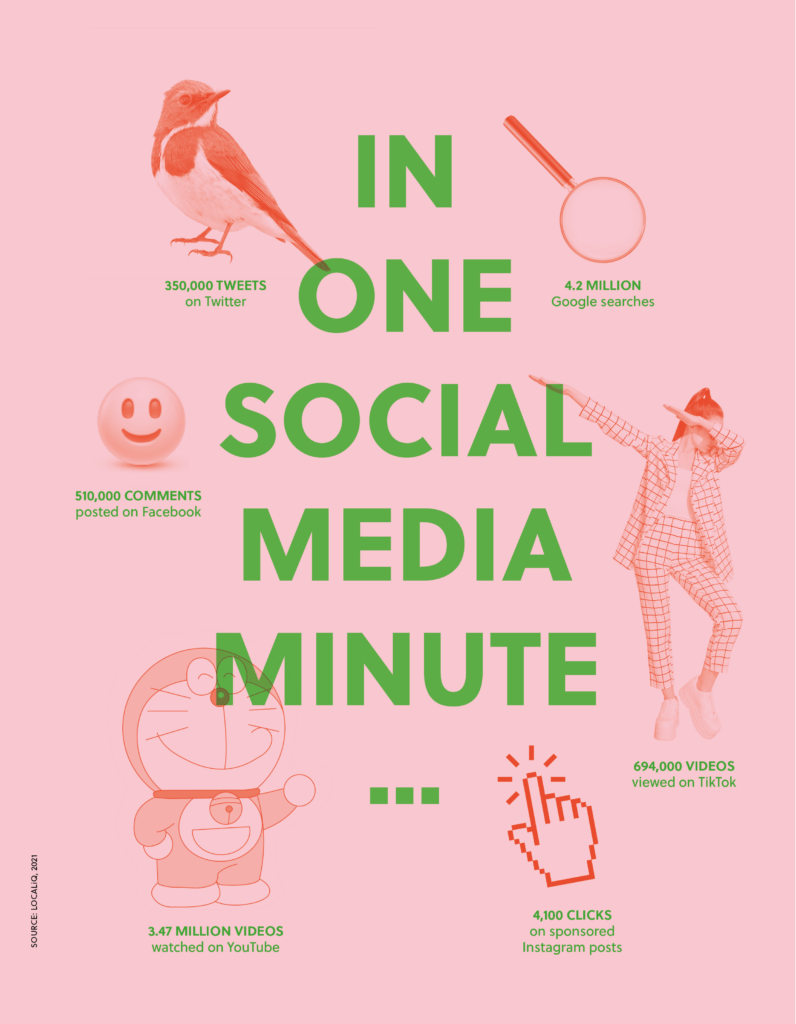

In a social media minute, there are 4.2 million Google searches, 510,000 comments posted on Facebook, 350,000 tweets on Twitter, 4,100 clicks on sponsored Instagram posts, 694,000 videos viewed on TikTok and 3.47 million videos watched on YouTube.

This is the arena where healthcare messaging and misinformation compete. Factual information, from symptoms through to lifestyle guidance, is a vital component of the quest to improve outcomes across all health conditions but it is at risk in hard-to-reach communities where there is less trust in official sources.

Polluted social media messaging has been raging throughout the pandemic with wild claims about drinking bleach or ethanol and, in July 2021, US President Joe Biden warned that the spread of covid-19 misinformation on social media was “killing people”.

Destructive content

Social media has long been a malign influence in non-communicable diseases (NCDs), giving platforms to damaging information in sensitive areas such as diet, obesity and mental health. Several societal and cultural factors can dilute or derail health communication allowing a social media torrent of good, bad and downright destructive content to cascade.

The covid-19 pandemic has crystallised the issue with misinformation (ill-guided repetition of myths and half-truths) radiating around the world and disinformation (the insidious manipulation of data and science) causing confusion and steering people away from life-saving vaccination programmes.

Not everyone is internet savvy or has the time or capabilities to fact-check everything they see. Some communities are distrustful of authority and official sources, while others are easily influenced by unfiltered internet content.

To tackle the spread of disinformation on their platforms, social media companies have signed up to the European Commission’s Code of Practice on Disinformation and have been required to submit reports on their efforts.

Rick Evans, social strategy director at UK healthcare communications agency 90ten, says the biggest challenge lies with the algorithms that tune content to a user’s browsing history. “If you are a young girl who has been looking at fad diets [popular diets that promise health benefits like weight loss but often lack scientific evidence] then you are more likely to receive dodgy diet advice and dubious information. It’s very much the quality of the information that drives the algorithm.”

Prejudices and truths

“The more you engage with disreputable sources, the more the channels will serve you up this type of information,” Evans says. “People who seek out or who maybe are more disposed to looking at information that is not scientifically or medically accurate are more likely to be exposed to more of the same that confirms prejudices and untruths. The problem is that positive, accurate information gets drowned out and that is particularly worrying around mental health and diet and obesity.”

Indeed, social media’s malign influence on covid-19 behaviour patterns should not be regarded as a hot streak that will cool and fade post-pandemic as recent research has indicated that exposure to pandemic misinformation is associated with a higher susceptibility to wider misinformation across other conditions.

This is a significant and lasting threat to healthcare literacy and behaviour. A 2020 study published in Royal Society Open Science demonstrated a clear link between susceptibility to misinformation and vaccine hesitancy and a reduced likelihood of complying with public health guidance.

Combatting misinformation

Health misinformation is far from a recent phenomenon as false and fake statements have been raging across the entire NCD landscape for years. “It has been out there for a long time with anti-vaccination movements and conspiracy theories existing way before the pandemic,” says Aleksandra Kuzmanovic from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) social media team, which is deploying a range of tactics to combat misinformation and leverage communication channels to spread accurate information.

“Just because there is a focus on covid-19 doesn’t mean that other areas, such as NCDs, are not being impacted. But it always spikes with a new virus and anything that turns people away from treatment or towards the wrong treatment can be devastating.”

The issue was made hugely evident when singer Nicki Minaj broadcast to her 22.6 million Twitter followers (the main WHO Twitter account has 10 million followers) that her cousin in Trinidad allegedly said he would not be vaccinated against covid-19 because “a friend got it and became impotent. His testicles became swollen. His friend was weeks away from getting married, now the girl called off the wedding”. There was no scientific basis to the claim but the tweet gained 100,000 likes and sparked an internet backlash against the vaccine.

Fears about the side effects are the main driver of public reticence to get vaccinated and the Africa Infodemic Response Alliance, which tracks dangerous content, has debunked more than 1,300 misleading reports through the pandemic.

“Social media has played a key role in spreading anxiety about the covid-19 outbreak, fake treatments, the rising number of deaths, and up until now covid vaccines. This has really made a number of people be hesitant on getting the vaccines,” Makinia Sylvia, a senior researcher at Africa Check, the independent fact checking agency.

The deluge of covid-19 misinformation is merely the latest in a procession of anti-vaccine campaigns. In 2003, a polio vaccination campaign was disrupted in northern Nigeria by a string of spurious claims that the vaccine was possibly being contaminated with anti-fertility agents. A 15-month boycott of the vaccine ensued and the country’s polio immunisation campaign was dealt a heavy blow. This boycott meant that by 2008 Nigeria alone accounted for 86% of all polio cases in Africa, and since the boycott the country has struggled to be declared polio free.

Evidence-based sources

A recent systematic review published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research confirmed the wide-reaching influence of misinformation on NCDs. It found that although the greatest concentration of false claims fell on vaccines, NCDs, drugs and smoking were also targeted. According to WHO, the pandemic has been a springboard for wider health misinformation, and it has stated: “The amount of misinformation surrounding NCDs has increased substantially during the covid-19 pandemic.”

Exposure to pandemic misinformation is associated with a higher susceptibility to wider misinformation across other conditions

Dr Nino Berdzuli, director of the Division of Country Health Programmes at the WHO Regional Office for Europe, adds: “False and inaccurate information related to the risk factors for NCDs is a huge challenge.

“And with people seeking dietary advice, lifestyle counselling and even treatment online, this can lead to serious consequences. It reveals the importance of having trustworthy, evidence-based sources for information on health which the public can trust and that will allow informed and sound decisions.”

The challenge is to ensure that accurate information is delivered across geographies and cultures by people, or organisations, that are trusted and relevant. WHO’s social media pandemic response has cleverly invoked popular children’s cartoon characters such as Peppa Pig, Baby Shark and Akilia on hand washing campaigns as well as rolling out heavy-hitting artists and political and sports figures.

The double Olympic marathon champion and world record holder, Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge, used his profile in September to urge youngsters to come forward for the jab, stating on television: “Please let us get vaccinated because you are our future. If you do not get vaccinated then you are ruining our future, we rely on you.”

Breaking the misinformation chain

WHO’s Kuzmanovic adds: “We have a broad approach, partnering with social media platforms, who are endeavouring to minimise misinformation, ambassadors, sports stars and celebrites and have partnered with Disney and cartoon characters that are popular in different countries.

“We are operating in a challenging environment, but we are making progress. It has been successful, given the levels of misinformation that are out there. We can always do more, but we are committed to giving people the information they need and help people stop the chain of misinformation transmission.”

The Journal of Medical Internet Research review also warned that false or misleading health information may spread more easily than scientific knowledge through social media. It called for more research to understand how misinformation infects health decision making and behaviours.

The big social media platforms are responding by collaborating with health organisations in different countries, and Google, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok and Microsoft follow the European Commission’s Code of Practice on Disinformation.

Positive power

The power of positivity and alternative routes of communication should not be neglected as crucial to prevention and control of NCDs. Indeed, the power of positivity was given centre stage when model Lila Moss, who is a type 1 diabetic, wore her insulin pump while walking down a fashion catwalk in a bikini. She shared the photo with her 200,000 Instagram followers, generating more than 60,000 likes and more than 1,600 positive comments.

Innovative ways of reaching groups who do not engage with social media is also a key weapon and success has been scored by holding events in neighbourhood settings and on public transport.

In Kenya, a door-to-door information programme to tackle vaccine hesitancy was launched and pop-up events in schools, churches and community centres have also been used. The country’s chief administrative secretary, Dr Mercy Mwangangi, comments: “We are now using what is known as a hybrid approach. We are going to the people, we are having outreaches, we are partnering with churches and different institutions to ensure that the vaccine is closer to Kenyans.”

There is no cure for the malady of misinformation and disinformation, but the antidote will need a new approach to social media and relentless efforts and co-ordination across health communities

Several healthcare systems in Europe partnered with Imams to make sure accurate messaging got through to hard-to-reach Muslim communities during the pandemic.

90ten’s Evans adds: “I have worked in the HIV sector and in many sub-Saharan programmes, SMS text messages have been very effective. Less people have internet access, but they do have phones and outreach workers have had good success with SMS.

“It is also important to partner with respectable voices, such as faith leaders, and it’s about using the right language that people can identify with and showing respect to the people you are trying to reach.”

A graphic example came when Portuguese superstar footballer Cristiano Ronaldo removed two Coca-Cola bottles placed in front of him at a European Championship press conference in June and replaced them with a bottle of water, an action seen by millions around the world.

The fight against misinformation will continue long after the pandemic has passed, and campaigners will need to evolve techniques and strategies to keep pace with a fast-changing technology.

Evans advocates greater resources being put into education, even adding digital literacy to the school curriculum, to equip future generations with the skills and awareness to navigate away from misinformation and disinformation.

The actions of the internet giants and how willing they are to sacrifice profit and tame algorithms so harmful content is eradicated or marginalised will have a huge impact on health outcomes.

There is no cure for the malady of misinformation and disinformation, but the antidote will need a new approach to social media and relentless efforts and co-ordination across health communities.

Misinformation spreads so quickly online, and it’s crucial to verify sources before believing or sharing anything. The digital world has made it easier than ever to access information, but it’s also made it harder to separate fact from fiction. This applies not just to news but also to everyday decisions, like where to eat, what to buy, or even where to shop. That’s why I love exploring unique local spots, especially when it comes to shopping in st augustine—discovering authentic boutiques, handcrafted goods, and hidden gems that you can trust. Nothing beats firsthand experiences and supporting businesses that bring real value to a community.